Bloom

These paintings invite joy and melancholy in fairly equal amounts. Of course, that is inherent in the nature of flowers… impossibly radiant, blooming one minute then tainted by forces beyond their control, wilting, fading, their sweet aroma dissipating as they begin to turn, becoming unwelcome.

But as much as these paintings have flowers as their subject, they are, as Juliet described of Romeo “a rose by any other name would smell so sweet.” For the inherent quality of these ‘flower paintings’ is less the flower and more the paint. Their essential character, like Montague, ought not to be captive of the name.

Each painter here uses their shared material in profoundly differing ways and yet each arrive at the conclusion that these fragile motifs insinuate something fundamental to our fugitive existence. But let’s not be so bleak… for as poignant as each is, there is a celebratory spirit that overcomes the rhythm of decay. Furthermore, their vivacity as paintings, their precociousness and their material poetry is really what is at stake.

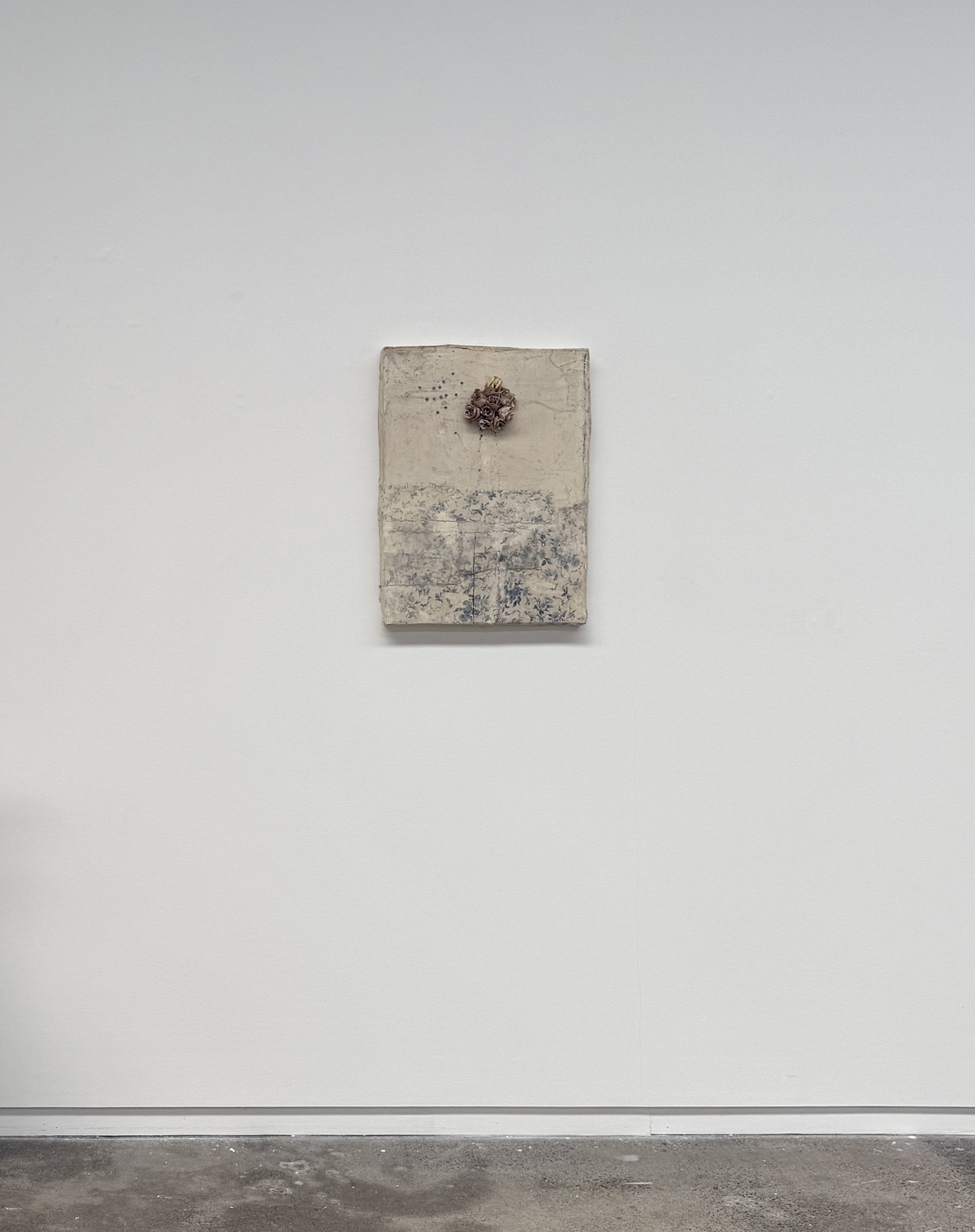

Lawrence Carroll’s Untitled 2014-17 will always be for Emma and I, one of the most poignant works we have ever presented. We had, on Lawrence’s invitation, journeyed to Bolsena, north of Rome and spent two days in his company, in his studio and in the extended embrace of his wife Lucy. Emma and I were charmed by them, by Lawrence, his humour, his ease and his insight – smitten by his work… and we remain so. Lawrence’s raw Arte Povera aesthetic cut a fresh and rough-hewn track right through the centre of our gallery. Then like a daylily he was gone. What we have in his absence is a sublime yet modest collage of the scavenging brilliance of Carroll. Flimsy cotton, plastic flowers and housepaint… no fine cedar stretchers here, no crisp folds of linen but there is everything one could ever desire and it exists to us as a memento vivere.

Bianca Raffaella’s paintings exist on the edge of visibility. Elusive, fleeting, dreamlike perhaps. She offers us a hint of physicality. Her blooms are barely there but what they repress in physicality they assert in atmosphere. Pigment brushes up against the linen in soft caresses that insinuate presence and form. Raffaella’s own vision impairment has ironically heightened her sensitivity, and these paintings demonstrate that the tools that we regard as crucial to recognition and apprehension, even sensation – can be substituted for other faculties if only we would close our eyes so as to see..

Gideon Rubin’s paintings share something of this understatement though his work is rooted in a knowing and astute description. He is however cautious about the amount of data required, preferring to compress his image making in favour of innuendo. Whether it is a flower, or an isolated figure, Rubin’s observation of deportment is perceptive and discerning. The undemonstrative brushwork that he employs is critical in his determination not to distract, to lead us away from the fundamentally human proposition that he makes evident with each painting. For all of this reductive clarity these are paintings that can seduce us with nostalgia, turn our heads with intimation, quicken our pulse with playful voyeurism; yet their magic lies in Rubin’s ability to make judgements about tone and placement. He and we understand that the success or otherwise depends on these being solved only as paintings.

And then there are the paintings of Niyaz Najafov. The antithesis to Raffaella’s delicacy and Rubin’s knowing observation. These full force paintings explode into existence. If Bianca’s paintings are on the edge of visibility, these are simply on the edge. These paintings are over-ripe, fecund, roiling with psychological vandalism. But amidst the intensity there is humour, doubtless dark but humour nonetheless. Niyaz’s flowers are dangerous, Triffid-like… cousins of Seymour’s demanding Venus flytrap in Little Shop of Horrors… stand close if you dare. Once the theatre of the work is understood then we are free to revel in the Soutine-like temerity of the pigment and the brushwork. There is no doubt that Najafov can draw, for his agitated line is crucial to the work, but it is the way that he masses pigment, pushing and tormenting it until it feels as if it could never have emerged from a tube, all smooth and alluringly viscous, that is most captivating.

Less voracious than Najafov but equally committed to speed and viscosity, the paintings of Robert Malherbe are most certainly the result of observation – but Malherbe’s eye is fast and restless. Like Rubin he is uploading data but doesn’t want to wait too long. Malherbe however does accumulate a great deal of memory in the end of his brush, and it becomes apparent the more we see. Like Rubin he is determined to solve the paintings on their own terms rather than be hostage to mere description, so that the works establish their own painterly veracity.

Aida Tomescu’s impressive diptych demonstrates a dramatic efflorescence – a flowering of pigment and energy across two open linen fields. This embrace of the linen as a foundational element in the spatial implications of the painting rather than an extension of the support has allowed Tomescu’s paintings to open, simultaneously outwards and inwards, establishing a physical and metaphorical space for the painting to build body and presence.

Rather than the more literal analogy of folds and petals, Tomescu delivers a folding of space where form and transition share in the ambition to make paintings of rare substance.